Regret in the Void: The Terrifying Truth Kevin Hines Learned Falling from the Golden Gate

Regret in the Void: How a Suicide Leap Became a Rallying Cry for Survival and Activism

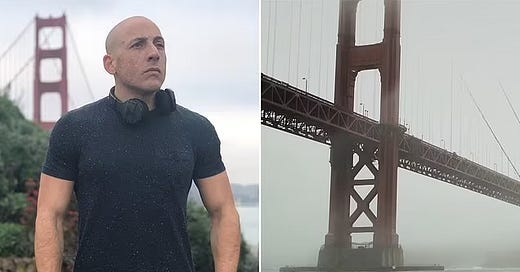

The Golden Gate Bridge isn’t just a postcard icon draped in San Francisco fog. It’s a grim magnet for the broken, a place where over 1,800 people have leaped to their deaths since it opened. Kevin Hines was 19 when he joined that grim tally on September 11, 2000. But his story isn’t about the jump—it’s about what happens before the fall, in the shadowed corners of a mind screaming in silence. Diagnosed with bipolar disorder at 17, Kevin wasn’t chasing death that day; he was fleeing a pain that convinced him he was a burden, a defect, a ghost already fading. This isn’t some polished tale of survival. It’s about the most horrifying split-second a human can experience: that void between choice and consequence where regret hits like a sledgehammer—and where Kevin learned a truth that would haunt him long after the water swallowed him whole.

Picture a teenager buying a bus ticket to the bridge, each step feeling like a march to his own execution. The fog, the roar of traffic, the tourists snapping photos—none of it mattered. Inside, a storm raged: voices whispering lies, psychosis twisting reality into a funhouse mirror of despair. What comes next isn’t inspiration. It’s a raw, unfiltered plunge into the physics of self-destruction, the alchemy of luck, and the chilling fact that sometimes, clarity arrives a heartbeat too late.

The Mental Maze: The Prison Before the Bridge

At 17, when most kids dream of prom or college, Kevin’s diagnosis of bipolar disorder felt less like a medical label and more like a life sentence. Imagine waking up every day trapped inside a broken radio—static hissing, volume blaring, signals crossing until you can’t tell reality from nightmare. He’d lock himself in his room, convinced he was a monster, a drain on everyone who loved him. The world saw a troubled teen; Kevin saw a ghost in the mirror, something too fractured to fix. It wasn’t sadness—it was a warzone in his mind, where hallucinations morphed into commandments: "You don’t deserve to breathe. End it."

By the morning of September 11, 2000, the battle was lost. He’d planned it coldly: ride the bus to the bridge, walk the span, find a spot where the fog hung thickest. No note, no grand gesture—just a quiet erasure. He’d packed his pockets with a phone and a suicide note, then boarded like a man heading to his funeral. What’s bone-chilling isn’t the act itself, but the eerie normalcy of it. He’d even asked a tourist to take his photo minutes before climbing the rail—a smile plastered on his face while inside, the voices screamed jump. This wasn’t courage. It was surrender to a lie his own brain had sold him: that disappearing would be a kindness.